“Don’t judge a day by the harvest you reap, but by the seeds that you plant.”

Robert Louis Stevenson

“Don’t judge a day by the harvest you reap, but by the seeds that you plant.”

Robert Louis Stevenson

“The most beautiful thing that we can experience is the mysterious…He to whom this emotion is a stranger is as good as dead”

Albert Einstein

“Personal relationships are the fertile soil from which all advancement, all success, all achievement in real life grow.”

Ben Stein

“If you are going through hell, keep going.”

Winston Churchill

“If history repeats itself, and the unexpected always happens, how incapable must Man be of learning from experience.”

George Bernard Shaw

“Successful leaders see the opportunities in every difficulty rather than the difficulty in every opportunity.”

Reed Markham

“It is unbecoming for young men to utter maxims.”

Aristotle

“Perpetual devotion to what a man calls his business, is only to be sustained by perpetual neglect of many other things.”

Robert Louis Stevenson

For many of you the next few days represent an opportunity to do something different with your minutes.

You have a choice what you do with those blocks of 60 seconds.

The worlds is busy doing all sorts of things, but what are you going to do?

As for me, no I’m not writing blog posts, I scheduled this one before the Christmas break. I’ll be following my usual holiday pattern and turning down the volume on my online interactions. I have the title music of a TV programme from my childhood ringing in my ears now “why don’t you…?”

One of the characteristics of an axiom is that it’s obviously true and as such you rarely question it.

I’ve subscribed to the view that some people are 10 times more productive than others for a long time – it has been obviously true.

I’ve subscribed to the view that some people are 10 times more productive than others for a long time – it has been obviously true.

As I look around the place where I work I can see that some people produce wildly more than others.

I’ve also worked on many projects where I’ve seen people who can clear the workload at an astonishing pace, they are obviously, noticeably more productive.

I was reminded of this axiom recently while reading a couple of articles by Venkatesh Raso on Developeronomics:

At the centre of the debate being had here is the idea of the 10x engineer:

The thing is, software talent is extraordinarily nonlinear. It even has a name: the 10x engineer (the colloquial idea, originally due to Frederick Brooks, that a good programmer isn’t just marginally more productive than an average one, but an order of magnitude more productive). In software, leverage increases exponentially with expertise due to the very nature of the technology.

While other domains exhibit 10x dynamics, nowhere is it as dominant as in software. What’s more, while other industries have come up with systems to (say) systematically use mediocre chemists or accountants in highly leveraged ways, the software industry hasn’t. It’s still a kind of black magic.

One of the reactions comes from Larry O’Brien knowing.net describing the 10X engineer like this:

This is folklore, not science, and it is not the view of people who actually study the industry.

Professional talent does vary, but there is not a shred of evidence that the best professional developers are an order of magnitude more productive than median developers at any timescale, much less on a meaningful timescale such as that of a product release cycle. There is abundant evidence that this is not the case: the most obvious being that there are no companies, at any scale, that demonstrate order-of-magnitude better-than-median productivity in delivering software products. There are companies that deliver updates at a higher cadence and of a higher quality than their competitors, but not 10x median. The competitive benefits of such productivity would be overwhelming in any industry where software was important (i.e., any industry); there is virtually no chance that such an astonishing achievement would go unremarked and unexamined.

In another article from 2008 Larry O’Brien gets into the specifics of programmer productivity:

That incompetents manage to stay in the profession is a lot less fun than a secret society of magical programmers, but the (sparse) data seem consistent in saying that while individuals vary significantly, the “average above-average” programmer will be only a small multiple (perhaps around three times) faster than the “average below-average” developer (see, for instance, Lutz Prechelt’s work at citeseer.ist.psu.edu/265148.html).

So, it would appear, there seems to be some disagreement on this axiom which is precisely why I started this series – how many of my axioms are really just nice ideas?

One of the problems with axioms is working out where I first came across them, this one is proving difficult to remember. I suspect that it comes from my old friends Tom DeMarco and Timothy Lister writing in Peopleware:

Three rules of thumb seem to apply whenever you measure variations in performance over a sample of individuals:

- Count on the best people outperforming the worst by about 10:1.

- Count on the best performer being about 2.5 times better than the median performer.

- Count on the half that are better-than-median performers out-doing the other half by more than 2:1.

Peopleware: Individual Differences

But where did this come from: "[this diagram], for example, is a composite of the findings from three different sources on the extent of variations among individuals". So it comes from research undertaken around 1984 on software programmers.

You may have notice that I was vague at the beginning of the post about who the 10X people were being compared with – the median, the worst? It was deliberate, because I didn’t know, the axiom had become degraded over time and I couldn’t be specific. I was confused, and after doing some digging, I don’t think I’m the only one.

DeMarco and Lister point to and reference some real research for 10X being between worst and best which seems like a safe place to be. Everyone seems to agree that there is an order of magnitude difference between median and worst so that seems like a safe place to be too.

I feel like I’m having to constrain my curiosity a bit because there would appear to be so much more to learn but my time is limited. So I’m sticking to the safe areas.

Whatever the true axiom, we all need to understand that there is a significant difference in people’s productivity (however you might be measuring productivity) which makes it’s vitally important that we get the right people doing the right things. But it’s also important that we understand what our 10X place is and seek to optimise our time there and try to remove the constraints that are keeping us from getting there (he writes after a day of endless interruptions and chats resulting in very little personal productivity ![]() ).

).

You’re sitting at your desk working away focussing in on a problem that’s been on your list to resolve for weeks.

You start to uncover the various layers of the problem ruling some things out, adding new things in.

You start to uncover the various layers of the problem ruling some things out, adding new things in.

This isn’t a simple problem, it’s a bit complicated and you feel a bit like you are Poirot unravelling a mystery. You’re starting to build a real sense of achievement.

You’re not sure how long you’ve been working on this problem but just at the point you are starting to see some light at the end of the tunnel your boss walks in and asks why, yet again, you haven’t provided your weekly status report. You explain that you’ve been very busy doing real work and didn’t think anyone read the status reports anyway.

After a two minute conversation you return to your problem, but you’ve lost the thread – "where was I again". You curse your boss. Your curse yourself for coming into the office today.

You start all over again trying to resolve this knotty little problem. It takes you an age to regain the concentration that you had.

This is such a common problem that we accept it as normal. People have even adapted their working habits to try and carve out some time to get some work done.

The interruptions abound – email, phones, instant messaging, social media, people, meetings. But what is the cost of those interruptions.

My axiom has always been that the cost of an interruption is 20 minutes.

I thought that I’d got the 20 minute part from a book called Peopleware by Tom DeMarco and Timothy Lister but I’ve recently been rereading it and actually it says this:

During single-minded work time, people are ideally in a state that psychologists call flow. Flow is a condition of deep, nearly meditative involvement…

Not all work roles require that you attain a state of flow in order to be productive, but to anyone involved in engineering, design, development, writing, or like tasks, flow is a must. These are high-momentum tasks. It’s only when you’re in flow that the work goes well.

Unfortunately, you can’t turn on flow like a switch. It takes a slow decent into the subject, requires fifteen minutes or more of concentration before the state is locked in. During this immersion period, you are particularly sensitive to noise and interruption. A disruptive environment can make if difficult or impossible to attain flow.

So where did I get 20 minutes from? Perhaps it’s just one of those things that changes in your mind over time? Not that it’s really that important, the significant factor here is that an interruption costs you significantly more than the length of the disturbance.

What Peopleware outlines is a theory called flow and the real question, therefore, is whether this theory is really the way our minds work.

The theory of flow appears to have been popularised by a Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi (no I don’t know how to say it either), in the 1990’s based on research from the 1960’s and 1970’s. The idea of being in a flow or in the zone or being in the groove have been around for much longer than that.

There appears to be a great deal of research undertaken which, for the most part, would appear to validate the theory outlined by Csikszentmihalyi. For once the article in wikipedia appears to be reasonably authoritative and well referenced.

So I’m reasonably happy that the axiom is true even if it’s not specifically 20 minutes, but we all work in the real world. How do we work in a way that minimises the impact.

The first part of resolving most problems is recognising that it exists, many people don’t.

The second part of overcoming a problem is to recognise the part that we are in control of. I don’t think I’m unique in being able to generate my own set of interruptions. There are also things that I can do to manage many of the disruptions.

There are all sorts of schemes that people use and I don’t think that there is one that suites everyone. The following mind map (not my own) reflects some of the things that I do:

I really like pictures.

The most visited page on this site is one about Rich Pictures.

I regularly pick out interesting Infographics.

One of my favourite books at home is called Information is Beautiful which is named after the popular website.

Why? Because “a picture is worth a thousand words”, or at least that’s the axiom I tell myself.

Why? Because “a picture is worth a thousand words”, or at least that’s the axiom I tell myself.

I wonder, though, whether this is really true.

If it were really true we’d spend much more time drawing, and far less time writing words. Yet writing words is what we do and do a lot (much like I’m doing now).

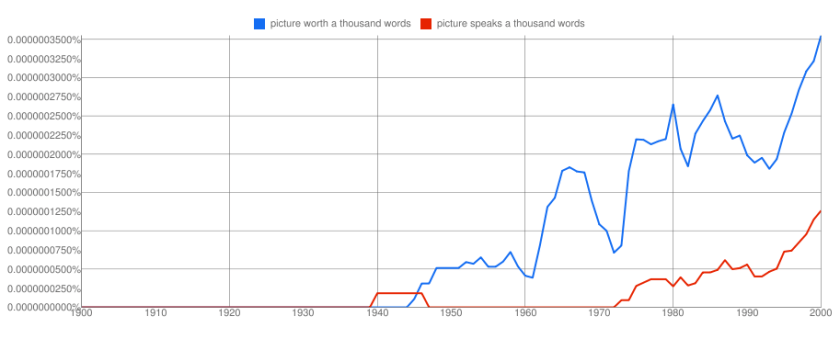

Many think that the saying is ancient and oriental, but the evidence for that is somewhat sketchy at least the literal translation. What can be said is that it was used in the 1920’s, became popular in the 1940’s and continues to be a preferred phrase. The variation on this “A picture speaks a thousand words” didn’t come until the 1970’s:

Just because something is popular, and just because it appears to be true doesn’t mean that it is true.

In order to assess the validity of the axiom I set off down the scientific route. What research was there for the value if diagrams?

If it were to be true then there would be some clear evidence for a picture being a much better way of communicating than a set of either spoken or written words.

I was always taught that there were three types of learners: visual learners, auditory (listening) learners and kinaesthetic (doing) learners. So I wondered whether there might be some mileage in the research done into that particular subject. If visual learners are stronger than auditory learners then it would add weight to the premise. But it turns out that learning styles might be one of my anti-axioms. So I gave that up as a dead-end.

My next port of call was to think of one particular diagram type and see whether there was any science behind the value of a particular technique.

Most of the pictures I draw are really diagrams with the purpose of communicating something.

As a fan of mind maps as a diagramming technique I wondered whether there was any clear evidence of their value. Back in 2006 Philip Beadle wrote an article in The Guardian on this subject and the use of mind maps in education:

The popular science bit goes like this. Your brain has two hemispheres, left and right. The left is the organised swot who likes bright light, keeps his bedroom tidy and can tolerate sums. Your right hemisphere is your brain on drugs: the long-haired, creative type you don’t bring home to mother.

According to Buzan, orthodox forms of note-taking don’t stick in the head because they employ only the left brain, the swotty side, leaving our right brain, like many creative types, kicking its heels on the sofa, watching trash TV and waiting for a job offer that never comes. Ordinary note-taking, apparently, puts us into a “semi-hypnotic trance state”. Because it doesn’t fully reflect our patterns of thinking, it doesn’t aid recall efficiently. Buzan argues that using images taps into the brain’s key tool for storing memory, and that the process of creating a mind map uses both hemispheres.

The trouble is that lateralisation of brain function is scientific fallacy, and a lot of Buzan’s thoughts seem to rely on the old “we only use 10% of the neurons in our brain at one time” nonsense. He is selling to the bit of us that imagines we are potentially super-powered, probably psychic, hyper-intellectuals. There is a reason we only use 10% of our neurons at one time. If we used them all simultaneously we would not, in fact, be any cleverer. We would be dead, following a massive seizure.

He goes further:

As visual tools, mind maps have brilliant applications for display work. They appear to be more cognitive than colouring in a poster. And I think it is beyond doubt that using images helps recall. If this is the technique used by the memory men who can remember 20,000 different digits in sequence while drunk to the gills, then it’s got to be of use to the year 8 bottom set.

The problem is that visual ignoramuses, such as this writer, can’t think of that many pictures and end up drawing question marks where a frog should be.

Oh dear, another cul-de-sac. In researching the mind-map though I did get to a small titbit of evidence, unfortunately from wikipedia (not always the most reliable source:

Farrand, Hussain, and Hennessy (2002) found that spider diagrams (similar to concept maps) had a limited but significant impact on memory recall in undergraduate students (a 10% increase over baseline for a 600-word text only) as compared to preferred study methods (a 6% increase over baseline).

That’ll do for me for now, it’s not “a thousand words” but it’s good enough for my purposes.

Why am I comfortable with just a small amount of evidence? Because this is one of those axioms where it’s not only about scientific proof.

Thinking about pictures in their broadest sense there are certainly pictures that would take more than a thousand words to describe them.

There are pictures that communicate emotions in a way that words would struggle to portray.

There are diagrams which portray a simple truth in a way that words would muddle and dilute.

In these situations the picture is clearly worth a lot of words, but our words would all be different. The way I would describe an emotional picture would be different to the words you would use. So it’s not about the number of words, but the number of different words.

This little bit of research has got me thinking though.

How often do we draw a diagram thinking that everyone understands it, but we’re really excluding the “visual ignoramuses” (as Philip Beadle describes himself). or the “visually illiterate” (as others describe it)?

In order to communicate we need to embrace both visual literacy and linguistic literacy in a way that is accessible to the audience. I used to have a rule in documentation, “every diagram needs a description”. The PowerPoint age has taken us away from that a bit and perhaps it’s time to re-establish it so that we can embrace the visual and the literal.

I’m happy to keep this as an axiom, but I need to be a bit more careful about where I apply it.